The relationship between music and math is well established and is universally accepted by musicologists and mathematicians alike. Rooted in facts and figures, their relationship explains not only the mathematical principles associated with pitch and harmony, but why my College Algebra and Music Theory grades are so strikingly similar.

And not in a good way.

More than a drive-by date, these two have been locked into a serious relationship since the beginning of time. In the book Music by the Numbers: From Pythagoras to Schoenberg, author Eli Maor states, "In Greek tradition, music ranked equal in status to arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy, which together comprised the quadrivium, the core curriculum of four disciplines that a learned person was expected to master." Music and math were not only hand-in-hand, but on equal footing.

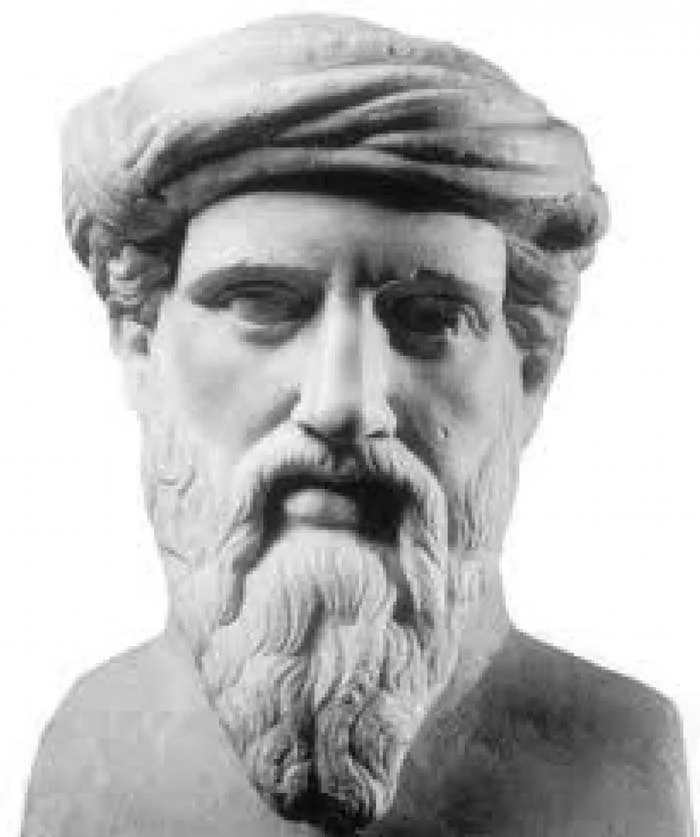

Though none of Pythagoras's original writings remain, his legacy of thought does. His philosophy of "numbers rule the universe" has became a rallying cry for generations of scientists and philosophers who share his view of the cosmos as being based on musical ratios or simple, elegant geometric figures. It was all part of Pythagoras's grand view of a universe ruled by beauty and harmony – known as musica universalis.

Pythagoras believed music to be universal and in all things.

Even in the planet Earth.

Musica universalis is the belief that mathematical relationships express qualities or "tones" of energy that manifest in numbers, angles, shapes, and sounds. Just as a pitch has a numeric frequency, Pythagoras believed that numbers emitted an energy of sound.

Crazy, right?

Pythagoras was the first to observe that the "pitch of a musical note is in inverse proportion to the length of the string that produces it, and that intervals between harmonious sound frequencies form simple numerical ratios." Pythagoras also proposed that the Sun, moon, and planets emit a "unique hum based on their orbital revolution, and that the quality of life on Earth reflects the tenor of celestial sounds it emits."

In other words, our planet is musical and responds to its inhabitant musicians. As long as we walk this planet, we can't escape its hum.

The Earth is humming? DOUBLE CRAZY, RIGHT?! I wonder what key we are in?

Music is numbers.

But, remember, according to Pythagoras,

numbers are music.

As music educators, this shouldn't come as a complete surprise. We live in a world of numbers. Numbers are how we staff our classes, chart our drill, determine instrumentation, and seat our ensembles. We even split our days into mathematically equal blocks of time called classes. Whether it's music or music education, everywhere you look, it's numbers, numbers, NUMBERS! (Marsha, Marsha, MARSHA!)

Musica universalists believe that everything emits music, even numbers and problems. Music that the ear can't hear, but the soul can. And it's not just in ancient times people believed that.

Schoenberg and Einstein, were also believers. They were contemporaries born within five years of each other to middle-class Jewish families. They were both self-educated and started their careers as low-level employees – Schoenberg as a bank clerk in Vienna, and Einstein as a clerk at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. Their mothers, both named Pauline, were steeped in classical music, so the two youngsters were raised in music-loving homes.

Schoenberg and Einstein espoused the relationship between math and music, with Schoenberg famously creating the twelve-tone row and Einstein stating, "I see my life in terms of music."

We want our students to learn math and science, and we require it from every student in the country. I believe and agree with that. But, I wonder if while talking about their science and math, we could also talk about their music when explaining. Not only would it make Pythagorean's Theorem more interesting, but also make Einstein's theory of relativity, more relative (see what I did there).

Pythagoras, Schoenberg, and Einstein. Pretty smart fellas I'd say.

Perhaps we should listen to what they have to say. Music is math; math is music. But what do I know? I'm not good at either.

At least now I know why!

Have a great week everyone!

- Scott